This article examines the psychological and behavioural implications of artificial intelligence integration in online learning environments, focusing on how algorithmic personalization, predictive feedback, and adaptive sequencing influence learner agency, cognitive autonomy, and self-regulation. Drawing on self-determination theory, cognitive psychology, and behavioural science, the study highlights both the supportive and constraining effects of AI-mediated learning. While adaptive systems can enhance perceived competence, reduce cognitive load, and support task alignment, they may also introduce subtle behavioural steering mechanisms that externalize regulation and diminish intrinsic motivation. The analysis shows that algorithmic nudging can recalibrate learners’ perceptions of control and responsibility, normalizing compliance with system-defined pathways. To address these tensions, the article proposes a psychologically grounded framework for ethically aligned AI-enhanced learning that balances adaptive scaffolding with reflective choice and exploratory engagement. By clarifying the cognitive and motivational mechanisms through which algorithmic systems reshape learner agency, the study offers design principles for autonomy-supportive AI-mediated learning environments.

Keywords: artificial intelligence in education, digital learning, learner autonomy, self-regulated learning, algorithmic personalization, AI ethics in education

____________________

Revista de Pedagogie Digitala – ISSN 3008-2013

2026, Vol. 5, Nr. 1, pp. 12-21

https://doi.org/10.61071/RPD.2619

HTML | PDF

____________________

Introduction

The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) across educational technologies has initiated a significant transformation in how learning environments interact with human cognition and behaviour. Online learning systems increasingly rely on algorithmic personalization, predictive analytics, and automated feedback to guide learner engagement, regulate performance, and optimize learning trajectories. While these developments promise efficiency and individualized support, they also raise critical psychological questions regarding learner agency, autonomy, and behavioural self-regulation (Selwyn, 2019; Williamson, 2017; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019; Bygstad et al., 2022).

From a psychological perspective, learning is not merely the acquisition of information but a complex interaction between motivation, cognition, emotion, and social context. AI-enhanced learning environments mediate these interactions by shaping attention, influencing decision-making, and structuring behavioural choices. Recommendation systems suggest content, adaptive platforms regulate pacing, and analytics dashboards provide continuous performance feedback. Such mechanisms can influence how learners perceive control over their learning process and how they interpret success, failure, and responsibility (Beer, 2018; Chen et al., 2022).

Recent advances in cognitive psychology indicate that environments which externalize decision-making processes can subtly reshape metacognitive awareness. When learners increasingly rely on algorithmic cues to determine what, when, and how to learn, self-monitoring processes may shift from internal regulation toward external validation. This transformation has direct implications for cognitive autonomy and the development of durable self-regulated learning strategies.

Psychological research and behavioural sciences has emphasized the importance of autonomy and self-regulation for sustained learning and well-being. Self-determination theory posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fundamental psychological needs that support intrinsic motivation and cognitive engagement (Deci & Ryan, 2008). When learning environments undermine these needs, learners may experience reduced motivation, increased dependence on external guidance, and diminished self-efficacy. AI-driven systems, while designed to support learners, may inadvertently shift motivational dynamics by externalizing control and normalizing algorithmic decision-making as an authoritative guide (Kizilcec et al., 2017).

Despite growing interdisciplinary interest in AI and education, psychological analyses of algorithmic mediation remain limited. Much of the existing literature focuses on technological performance or educational outcomes, leaving the behavioural and cognitive consequences underexplored (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020). This article addresses this gap by examining how algorithmic mediation reshapes learner agency and cognitive autonomy within AI-enhanced online learning environments.

The study pursues three objectives: (1) to analyse algorithmic mediation through established psychological and behavioural frameworks, (2) to identify the cognitive and motivational mechanisms affected by AI-driven personalization, and (3) to propose a psychologically grounded framework for ethically aligned AI-mediated learning.

1. Algorithmic Mediation from a Psychological Perspective

Algorithmic mediation refers to the process by which computational systems intervene in human behaviour by filtering information, guiding choices, and shaping feedback loops (Gillespie, 2014).

AI-enhanced learning environments rely on continuous data collection to model learner behaviour and predict future actions. These models inform adaptive interventions that aim to optimize engagement and performance. From a behavioural psychology perspective, such interventions resemble operant conditioning mechanisms, where feedback and reinforcement shape behaviour over time (Skinner, 1953). However, unlike traditional instructional feedback, algorithmic mediation operates continuously and often invisibly.

Cognitive psychology highlights that human decision-making is highly sensitive to contextual cues and default options. When algorithms recommend specific learning paths or prioritize certain tasks, they alter the cognitive environment in which learners operate. This can reduce cognitive load but may also limit exploratory behaviour and metacognitive reflection (Kahneman, 2011).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study adopts a conceptual-analytical research design grounded in psychological and behavioural science literature. Rather than collecting empirical data, the research synthesizes theoretical models and empirical findings from psychology, education, and human–computer interaction to construct an integrative framework for understanding algorithmic mediation in learning environments.

2.2. Data Sources and Selection Criteria

Sources were selected from peer-reviewed journals in psychology, behavioural sciences, and educational research. Inclusion criteria focused on studies addressing learner agency, self-regulation, autonomy, algorithmic decision-making, and AI-mediated behaviour. Foundational psychological theories were included to ensure theoretical coherence (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020). This study follows a conceptual integrative review methodology rather than a systematic review protocol. Sources were selected through purposive sampling from major psychology and educational research databases to ensure theoretical depth and interdisciplinary relevance.

2.3. Analytical Procedure

The analysis proceeded in three stages: (1) identification of key psychological constructs relevant to AI-mediated learning, (2) mapping of algorithmic mechanisms onto cognitive and behavioural processes, and (3) synthesis into a conceptual framework emphasizing learner agency and autonomy (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020).

2.4. Conceptual Data Visualization

The figures and tables presented in this study are conceptual data visualizations derived from synthesized patterns in the psychological and behavioural sciences literature. Rather than representing empirical measurements from a single dataset, these visualizations serve an explanatory function, illustrating theoretically grounded relationships between algorithmic guidance, learner autonomy, self-regulation, and motivation. Such an approach is consistent with conceptual research methodologies in psychology, where visual models are used to clarify mechanisms, support theoretical interpretation, and enhance analytical transparency.

3. Results

The analysis reveals three primary psychological effects of algorithmic mediation in online learning environments.

First, AI-driven personalization enhances perceived competence by aligning tasks with learner performance levels. Learners often report increased clarity and reduced frustration when content difficulty is adjusted dynamically (Kizilcec et al., 2017; Siemens & Baker, 2012).

Second, continuous algorithmic feedback influences self-regulation patterns. While dashboards and predictive alerts can support goal monitoring, they may also externalize regulation, reducing learners’ reliance on internal metacognitive strategies (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020; Järvelä et al., 2023).

Third, algorithmic guidance reshapes autonomy perceptions. Learners frequently follow recommended pathways without questioning underlying assumptions, indicating a shift from self-directed exploration toward compliance with system-defined norms (Rouvroy & Berns, 2013).

3.1. Psychological Patterns of Algorithmic Guidance and Learner Autonomy

Behavioural patterns synthesized across AI-mediated learning studies indicate a systematic relationship between the intensity of algorithmic guidance and learners’ perceived autonomy.

Beyond qualitative synthesis, behavioural patterns observed across AI-mediated learning studies indicate a systematic relationship between the degree of algorithmic guidance and learners’ perceived autonomy and self-regulatory capacity. Environments characterized by low levels of algorithmic intervention tend to preserve exploratory behaviour and intrinsic motivation, albeit with increased cognitive demands. Conversely, highly guided environments reduce cognitive load but simultaneously constrain autonomous decision-making.

Psychological evidence suggests that moderate algorithmic guidance may represent an optimal balance. At this level, learners benefit from adaptive scaffolding while retaining meaningful control over pacing and learning strategies. Excessive guidance, however, is associated with a decline in perceived autonomy and increased reliance on external regulation, consistent with self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

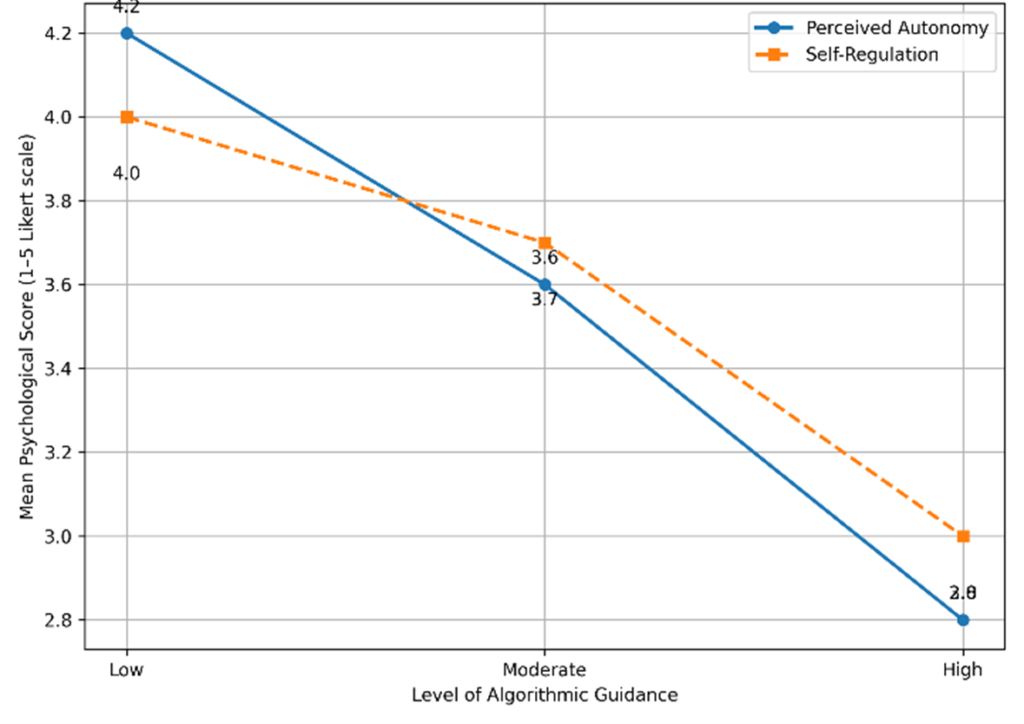

Figure 2 visualizes this relationship by illustrating changes in perceived autonomy and self-regulation across varying levels of algorithmic guidance. Figures 1 and 2 present conceptual models derived from the synthesized literature rather than empirical datasets. They illustrate theoretically grounded relationships identified across multiple studies in psychology and behavioural science.

Figure 1

Psychological effects of algorithmic guidance on online learners

As shown in Figure 1, increasing levels of algorithmic guidance are associated with a gradual decline in perceived learner autonomy and a parallel reduction in self-regulated learning behaviours. While moderate guidance appears to support regulatory balance, high levels of algorithmic control correspond to increased external regulation and diminished autonomous engagement.

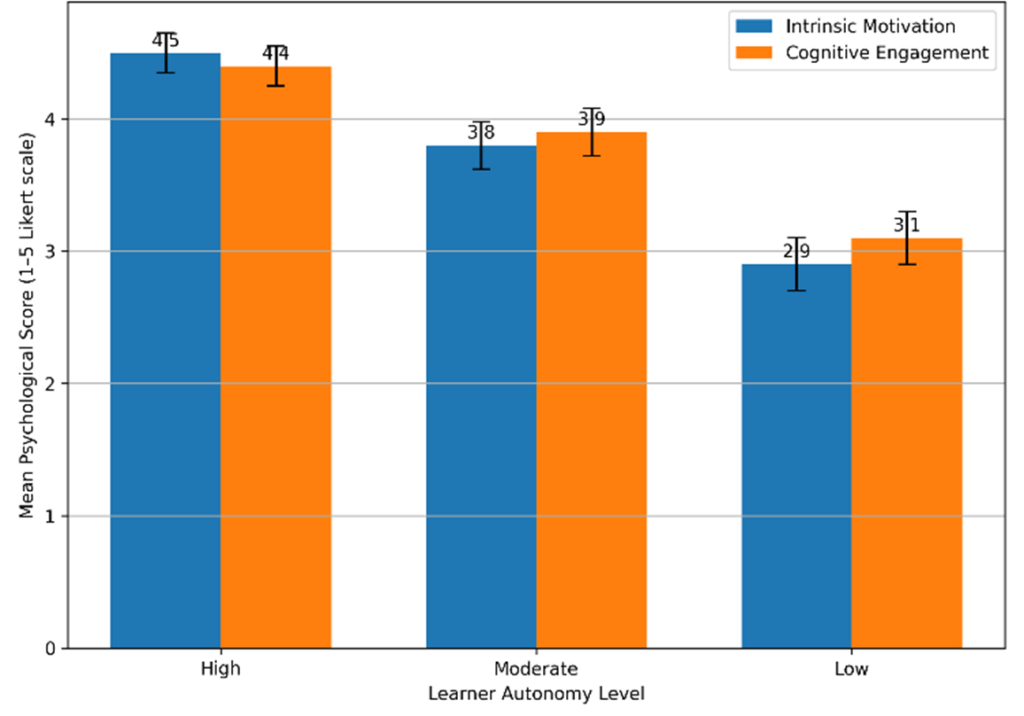

Figure 2

Relationship between learner autonomy and intrinsic motivation

Figure 2 illustrates the association between perceived learner autonomy and intrinsic motivation in AI-mediated learning environments. Higher levels of autonomy correspond to stronger intrinsic motivation, while reduced autonomy is associated with motivational decline, consistent with self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Together, Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the psychological trade-offs inherent in algorithmically mediated learning environments. While adaptive systems can enhance efficiency and task alignment, increased algorithmic guidance is associated with declining learner autonomy and reduced intrinsic motivation. These patterns suggest that algorithmic personalization, if not carefully designed, may shift learners from self-regulated engagement toward externally regulated compliance. The following discussion interprets these findings within established psychological and behavioural frameworks (Floridi & Cowls, 2019; Rouvroy & Berns, 2013).

Table 1

Comparative overview of major psychological frameworks relevant to AI‑mediated learning

| Theory | Core Constructs | Mechanisms of Regulation | Implications |

| Self-Determination Theory | Autonomy, competence, relatedness | Internal motivation, need satisfaction | Algorithms may support or undermine autonomy |

| Cognitive Load Theory | Working memory limitations | Decision simplification, reduced load | Adaptive pacing improves clarity but may constrain exploration |

| Behavioural Reinforcement | Rewards, conditioning | Feedback loops | Metrics may increase compliance-driven behaviour |

| Algorithmic Governmentality | Data-driven steering | Nudging, modulation | Risk of reduced cognitive autonomy |

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the main psychological frameworks that inform the analysis of AI-mediated learning environments. Each theory highlights distinct mechanisms through which learners regulate their cognition and behaviour, and therefore helps to clarify how algorithmic personalization may influence motivation, autonomy, and regulatory processes. Self-Determination Theory emphasizes the centrality of autonomy and intrinsic motivation, whereas Cognitive Load Theory focuses on how adaptive scaffolding shapes mental effort and task clarity. Behavioural Reinforcement models explain how feedback loops can condition learner responses, while Algorithmic Governmentality illustrates how data-driven nudging can subtly steer decision-making. Together, these frameworks reveal both the supportive and potentially constraining effects of algorithmic systems on learner agency (Floridi & Cowls, 2019; Rouvroy & Berns, 2013).

3.2. Behavioural Interpretation of Algorithmic Feedback Loops

Algorithmic feedback systems function as continuous behavioural regulators, shaping learners’ actions through real-time performance indicators and adaptive prompts. From a behavioural psychology perspective, these systems resemble reinforcement schedules that condition responses over time. Learners adapt not only to content but also to the expectations encoded in algorithmic metrics (Skinner, 1953).

This conditioning effect has important implications. While structured feedback enhances persistence and task completion, it may also reduce metacognitive engagement when learners internalize algorithmic judgments as authoritative. Over time, learners may shift from reflective self-monitoring to reactive compliance, prioritizing metric optimization over conceptual understanding (Ifenthaler & Yau, 2020; Skinner, 1953).

4. Discussion

These findings align with psychological theories emphasizing the importance of autonomy and self-regulation for meaningful learning. While AI-mediated personalization often supports competence by improving task-learner fit and reducing frustration, its effects on autonomy are more ambivalent. Excessive algorithmic steering may undermine intrinsic motivation by replacing self-initiated goals with externally imposed structures (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Recent scholarship on generative AI in education further suggests that conversational systems can scaffold goal-setting, strategy selection, and feedback-seeking – yet the same scaffolds can become “default authorities” if learners treat AI outputs as prescriptions rather than prompts for deliberation (Xia et al., 2025).

From a behavioural science perspective, algorithmic nudging functions as a subtle form of behavioural governance. Learners adapt behaviour in response to performance metrics and predictive feedback, often without conscious deliberation, which may normalize compliance with algorithmic expectations and weaken reflective self-monitoring (Floridi & Cowls, 2019; Rouvroy & Berns, 2013). Critically, contemporary reviews of educational chatbots report that many implementations are evaluated primarily through short-term perceptual outcomes and are frequently deployed without a robust pedagogical-theory basis – conditions that increase the risk that “what works” in the moment becomes a compliance engine rather than a learning ecology that cultivates agency (Debets et al., 2025).

A key psychological mechanism here is authority transfer: when recommendation logic is opaque, learners may infer objectivity and inevitability, reducing epistemic friction and bypassing metacognitive checking. Evidence from learning analytics dashboard research indicates that dashboards can support phases of self-regulated learning by making study behaviour visible – yet the design challenge is precisely to ensure that visibility translates into interpretation and planning rather than passive monitoring (de Vreugd et al., 2024). In parallel, explainable AI research in educational technologies shows that domain-specific explanations can strengthen trust and acceptance among teachers, implying that explanation is not simply a UX feature but a governance mechanism that helps preserve human judgment (Feldman-Maggor et al., 2025).

Table 2

Psychological effects of algorithmic mediation on learner behaviour

| Psychological Dimension | Low Algorithmic Guidance | Moderate Algorithmic Guidance | High Algorithmic Guidance |

| Perceived autonomy | High | Moderate-high | Low |

| Self-regulated learning | High but effortful | Optimally supported | Externally driven |

| Cognitive load | High | Balanced | Low |

| Intrinsic motivation | Strong | Sustained | Reduced |

| Behavioural compliance | Low | Moderate | High |

Table 2 may be interpreted as a directional effect matrix linking varying levels of algorithmic guidance to shifts across five interrelated psychological dimensions. Rather than demonstrating a linear “more guidance equals better outcomes” relationship, the pattern resembles a trade-off curve, with an apparent regulatory optimum at moderate levels of guidance. As algorithmic intensity increases, perceived autonomy declines progressively, moving from high under minimal guidance to moderate-high under balanced support and ultimately to low under strong system control. Self-regulated learning follows a parallel transformation: initially high but effortful when internally driven, it becomes optimally scaffolded under moderate guidance before transitioning into externally driven regulation when algorithmic direction dominates. Cognitive load, by contrast, decreases steadily from high to balanced to low, signaling increased efficiency; however, these gains co-vary with reductions in autonomous engagement. Intrinsic motivation exhibits a maintenance–erosion trajectory – remaining strong under low guidance, sustained under moderate support, and reduced under high control – consistent with self-determination theory’s prediction that motivation deteriorates when perceived control shifts outward (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Meanwhile, behavioural compliance increases across guidance levels, suggesting that exploratory, self-initiated behaviour is gradually displaced by norm-following responsiveness to algorithmic cues. Taken together, these converging patterns suggest a threshold effect: beyond moderate guidance, further reductions in cognitive load appear to be offset by disproportionate losses in autonomy and intrinsic motivation, accompanied by rising compliance. This configuration aligns with recent systematic review evidence indicating that many chatbot deployments prioritize short-term performance metrics while under-theorizing longer-term psychological and behavioural consequences, thereby reinforcing the need to evaluate AI systems not solely by task efficiency but by their impact on autonomy and self-regulatory development (Debets et al., 2025).

The implications intensify in the humanities and interpretive social sciences, where learning outcomes are not only procedural proficiency but also epistemic agency – the capacity to generate, contest, and justify interpretations. Digital humanities scholarship has argued for a human-centered AI curriculum that foregrounds civic and interpretive dimensions of AI, precisely to prevent automation from becoming an epistemic authority that narrows critical inquiry (Chun & Elkins, 2023). In writing pedagogy, generative AI has been framed as “critical play,” where the educational value depends on designing interactions that keep students in an ethically reflective, rhetorically aware stance rather than outsourcing invention and judgment (Colby, 2025). This aligns with Table 2’s warning signal: high guidance can suppress divergence, while moderate guidance can sustain motivation and reflection if learners are invited to interrogate outputs and justify choices.

The discussion therefore underscores the need for psychologically informed AI systems that balance adaptive support with opportunities for autonomy, reflection, and epistemic agency. At the policy layer, UNESCO’s guidance on generative AI emphasizes a human-centered vision with attention to governance, capacity-building, and ethical risks (Miao & Holmes, 2023). At the competence layer, responsible generative AI literacy has been framed as more than “effective prompting,” requiring critical awareness of how algorithmic systems shape information, decision-making, and responsibility – an orientation consistent with protecting autonomy under algorithmic mediation (Cox, 2024). Finally, systematic evidence on AI chatbots highlights both benefits and persistent concerns (e.g., reliability, bias, and governance), reinforcing the need to evaluate psychological mechanisms of reliance and self-regulation rather than treating AI assistance as neutral support (Labadze et al., 2023).

This dynamic raises ethical concerns not only about transparency and consent, but also about cognitive autonomy – the learner’s capacity to initiate, regulate, and evaluate learning independently. Psychology thus provides a critical lens for evaluating the long-term consequences of AI-enhanced learning design, and Table 2 offers a usable interpretive template: design for moderate, explainable, overridable guidance that reduces load without converting learning into managed compliance.

This article advances the field by reframing algorithmic personalization not as a binary support/control variable, but as a psychologically mediated regulatory gradient with identifiable autonomy thresholds.

Conclusions

This article examined algorithmic mediation in AI-enhanced online learning environments through a psychological and behavioural sciences lens. The analysis demonstrates that algorithmic personalization and continuous feedback can enhance perceived competence and streamline learning processes, yet may also constrain cognitive autonomy when guidance becomes overly prescriptive, opaque, or optimization-driven. Recent empirical and synthetic research confirms that while adaptive systems improve short-term engagement and performance, they may simultaneously externalize regulatory processes and attenuate learners’ capacity for autonomous planning and reflective judgment (Achuthan, 2025; de Vreugd et al., 2024; Kleimola, 2024).

Beyond individual-level effects, these dynamics carry significant institutional and policy implications. As AI systems increasingly mediate assessment, feedback, and learning analytics, educational institutions bear responsibility for ensuring that algorithmic infrastructures align with human-centred educational values. Emerging international governance frameworks emphasize the need to safeguard learner agency, protect data privacy, and promote ethical literacy in the deployment of generative AI and analytics-driven systems (Miao & Holmes, 2023; Vidal et al., 2023). Institutional policies must therefore move beyond reactive regulation and toward proactive, psychologically informed governance models.

From a design perspective, the findings support a shift away from optimization-centric architectures toward autonomy-supportive AI systems. Such systems should integrate explainability features that communicate recommendation rationales, configurable levels of scaffolding, and reflective interfaces that encourage learners to monitor, evaluate, and adjust their strategies rather than defer judgment to algorithmic outputs. Recent evidence suggests that explainable and configurable AI systems enhance trust, preserve professional judgment, and mitigate over-reliance on automated recommendations (Feldman-Maggor et al., 2025; Xia et al., 2026).

Looking forward, future research should empirically investigate the longitudinal effects of algorithmic guidance on intrinsic motivation, epistemic agency, and self-regulated learning resilience across diverse learner populations and disciplinary contexts. This is particularly urgent as generative AI tools and conversational agents rapidly scale within formal education, reshaping how learners plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning (Labadze et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2026). Understanding these long-term psychological consequences is essential not only for effective instructional design but for preserving human agency in increasingly data-driven learning ecologies.

References

Achuthan, K. (2025). Artificial intelligence and learner autonomy: A meta-analysis of self-regulated and self-directed learning. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1738751. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1738751

Beer, D. (2018). The data gaze: Capitalism, power and perception. Sage.

Bygstad, B., Øvrelid, E., Ludvigsen, S., & Dæhlen, M. (2022). From dual digitalization to digital learning space: Exploring the digital transformation of higher education. Computers & Education, 182, 104463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104463

Calboli, S. (2025). Autonomy and AI nudges: Distinguishing concepts and highlighting AI’s advantages. Philosophy & Technology, 38, Article 116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-025-00940-2

Chun, J., & Elkins, K. (2023). The crisis of artificial intelligence: A new digital humanities curriculum for human-centred AI. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 17, 147-167. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2023.0310

Colby, R. S. (2025). Playing the digital dialectic game: Writing pedagogy with generative AI. Computers and Composition, 75, 102915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2025.102915

Cox, A. (2024). Algorithmic literacy, AI literacy and responsible generative AI literacy. Journal of Web Librarianship. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2024.2395341

Debets, T., Banihashem, S. K., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., Vos, T. E. J., Maillette de Buy Wenniger, G., & Camp, G. (2025). Chatbots in education: A systematic review of objectives, underlying technology and theory, evaluation criteria, and impacts. Computers & Education, 226, 105323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2025.105323

de Vreugd, L., van Leeuwen, A., Jansen, R. S., & van der Schaaf, M. (2024). Learning analytics dashboard design and evaluation to support student self-regulation of study behaviour. Journal of Learning Analytics, 11(3), 249-262. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2024.8529

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182-185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin’s Press.

Feldman-Maggor, Y., Cukurova, M., Kent, C., & Alexandron, G. (2025). The impact of explainable AI on teachers’ trust and acceptance of AI EdTech recommendations: The power of domain-specific explanations. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-025-00486-6

Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2019). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society (pp. 167-194). MIT Press.

Ifenthaler, D., & Yau, J. Y.-K. (2020). Utilising learning analytics for study success: Reflections on current empirical findings. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09788-z

Järvelä, S., Kirschner, P. A., Panadero, E., Malmberg, J., Phielix, C., Jaspers, J., Koivuniemi, M., & Järvenoja, H. (2023). Enhancing socially shared regulation in collaborative learning groups: Designing for collective metacognition. Educational Psychologist, 58(1), 1-18. 10.1007/s11423-014-9358-1

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behaviour and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 104, 18-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.10.001

Kleimola, R. (2024). Promoting higher education students’ self-regulated learning through learning analytics: A qualitative study. Education and Information Technologies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12978-4

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2023). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20, 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00426-1

Miao, F., & Holmes, W. (2023). Guidance for generative AI in education and research. UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.54675/EWZM9535

Rouvroy, A., & Berns, T. (2013). Algorithmic governmentality and prospects of emancipation. Réseaux, 177(1), 163-196.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Selwyn, N. (2019). Should robots replace teachers? Artificial intelligence and the future of education. Polity Press.

Siemens, G., & Baker, R. S. J. d. (2012). Learning analytics and educational data mining: Towards communication and collaboration. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 252-254. https://doi.org/10.1145/2330601.2330661

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behaviour. Macmillan.

Vidal, Q., Vincent-Lancrin, S., & Yun, H. (2023). Emerging governance of generative AI in education. In OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an effective digital education ecosystem. OECD Publishing.

Xia, Q., Liu, Q., Tlili, A., & Chiu, T. K. F. (2025). A systematic literature review on designing self-regulated learning using generative artificial intelligence and its future research directions. Computers & Education, 240, 105465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2025.105465

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

____________________

Note

Generative artificial intelligence tools were used exclusively within the pedagogical design examined in this study to analyse learner interaction with AI systems. The manuscript itself was independently conceived, written, and critically developed by the author. No AI system generated the scholarly argumentation or conclusions presented herein.

Author:

Cristina-Georgiana Voicu

voicucristina2004@yahoo.fr

Titu Maiorescu Secondary School (Iași, Romania)

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9299-6551

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9299-6551

Author Biography:

Cristina-Georgiana Voicu is a senior educator at Titu Maiorescu Secondary School in Iași, Romania, and an independent researcher holding a PhD in Philology from Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași. Her work focuses on educational psychology, learner autonomy, self‑regulated learning, and the cognitive implications of AI in digital education. She has participated in multiple national and international research and educational projects, including Erasmus+ initiatives on digital transformation and inclusion. Her research contributes to understanding algorithmic mediation, cognitive autonomy, and ethical AI‑enhanced learning environments.

____________________

Received: 15.01.2026. Accepted and published: 20.02.2026

© Cristina-Georgiana Voicu, 2026. Published by the Institute for Education (Bucharest). This open access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence CC BY, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited:

Citation:

Voicu, C.-G. (2026). Algorithmic Mediation, Learner Agency, and Cognitive Autonomy in AI-Enhanced Online Learning Environments. Revista de Pedagogie Digitala, 5(1) 12-21. Bucharest: Institute for Education. https://doi.org/10.61071/RPD.2619